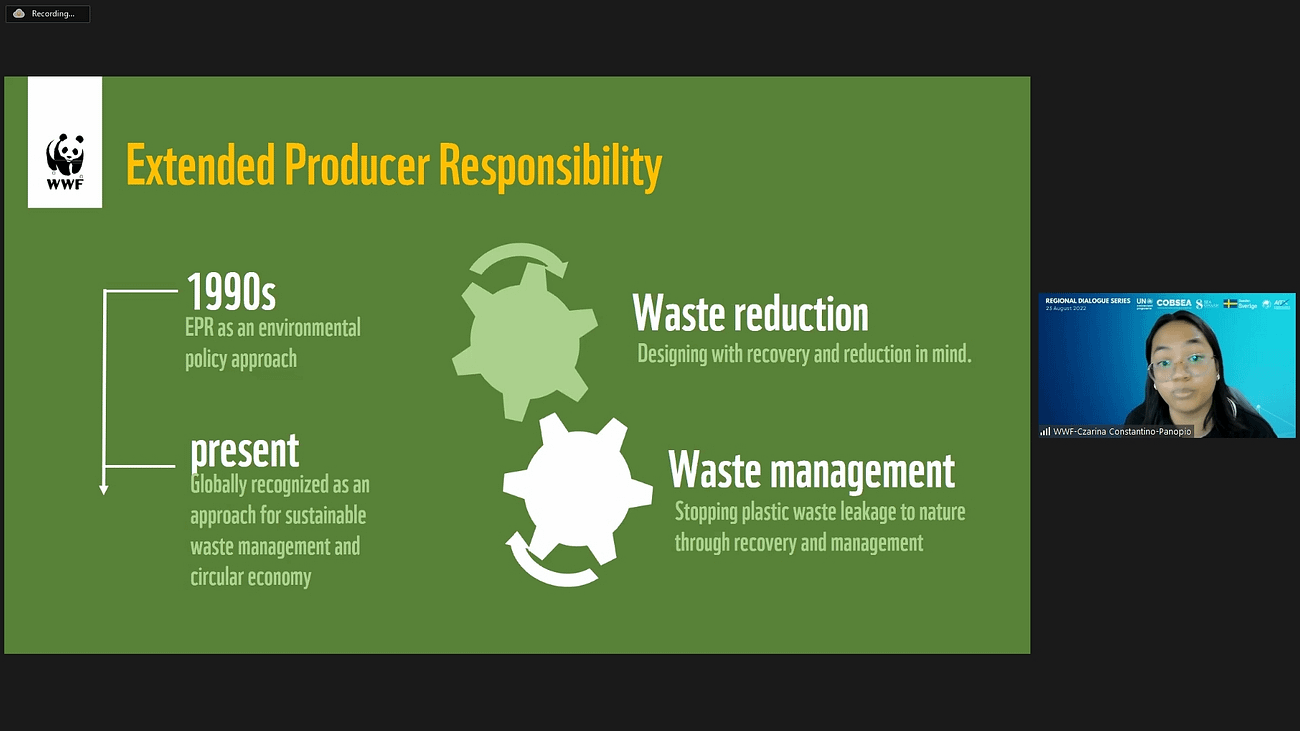

A Dialogue on Extended Producer Responsibility & Training on Human Rights Based Approach in the Plastic Value Chain

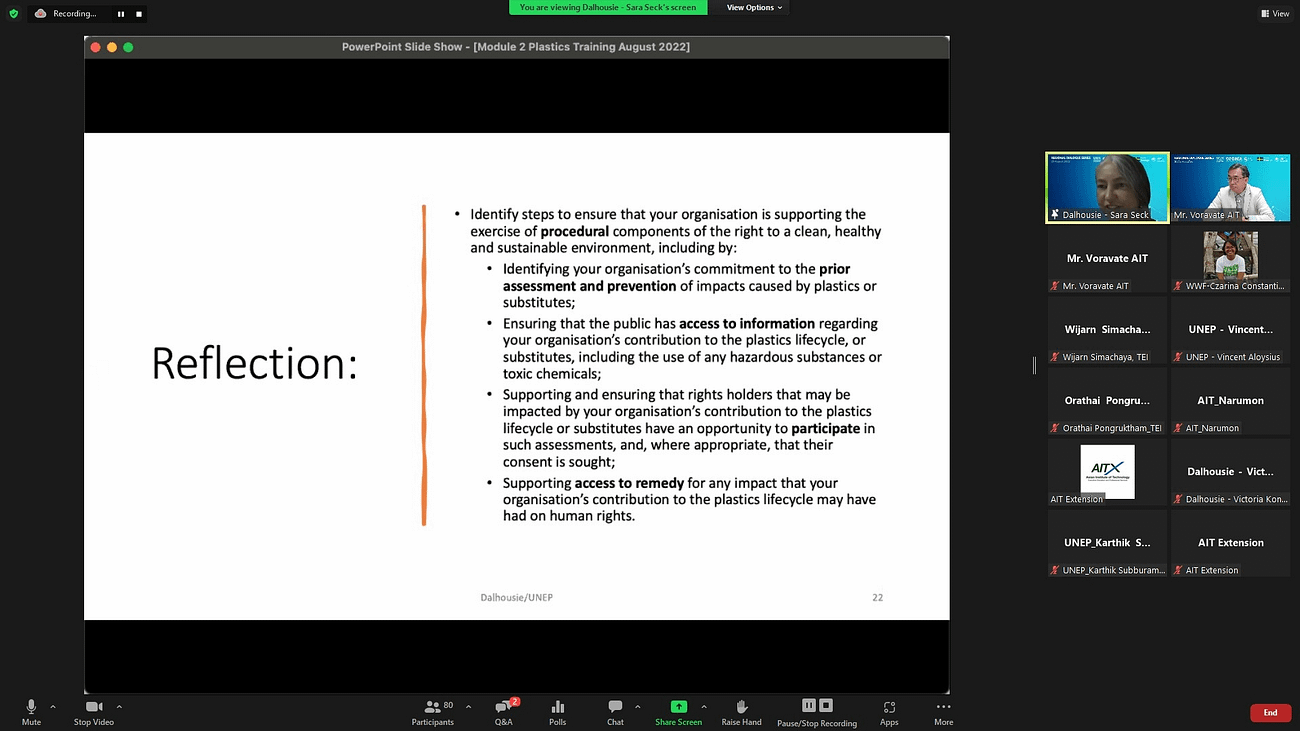

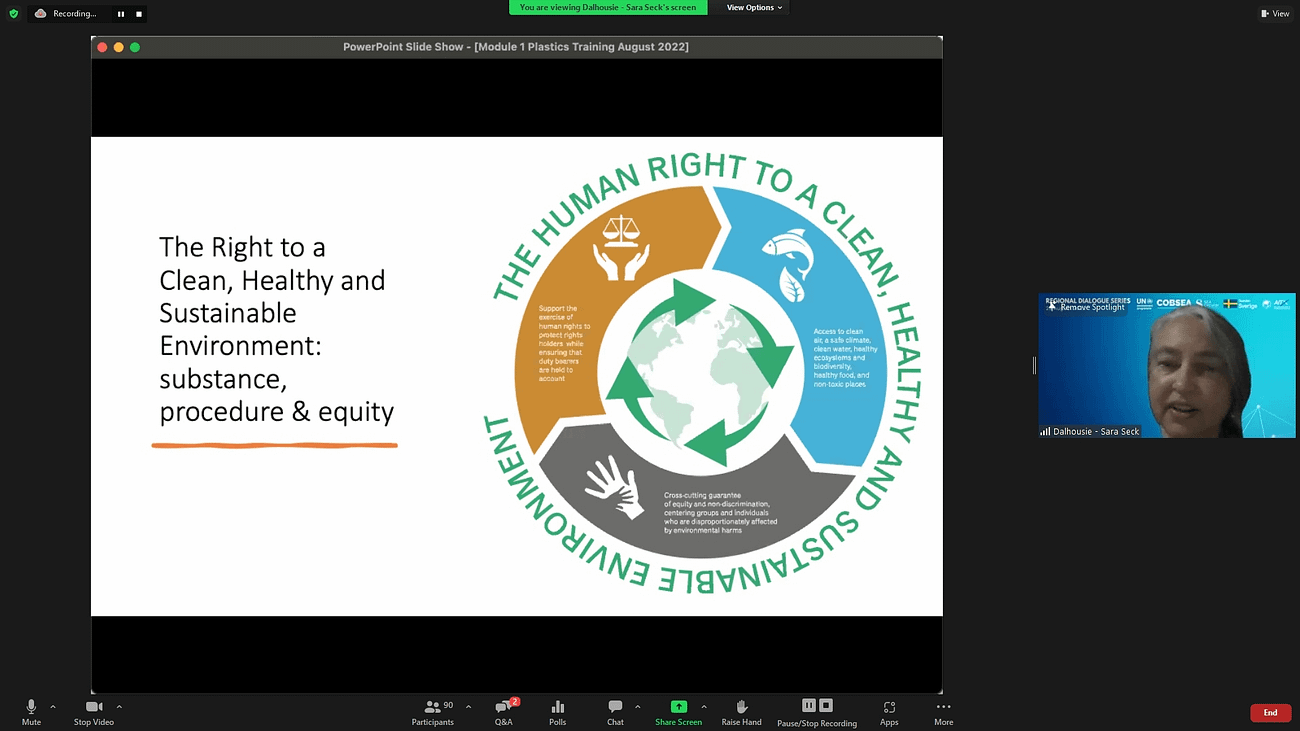

UN Environment Programme (UNEP), in close collaboration with AIT Extension, Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), will organize the first regional dialogue series which compose of two sub-activities, namely (1) a Training Session on Human Rights Based Approach (HRBA) in the Plastic Value Chain and (2) a Regional Dialogue on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Both events are scheduled on Tuesday, 23rd August 2022.

SEA circular project aims to reduce plastic pollution and its impact through a multi-sectoral approach, working with actors across the value chain – from policy makers to communities. The project strives to promote market-based solutions and enable policies to end plastic pollution at source – ensuring impact that is sustainable and scalable.

One of the components of the SEA circular are series of regional dialogues. The regional dialogues are meant to act as a platform to exchange experience, enable collaboration and empower stakeholders to take actions. Each program shall combine a dialogue session and the launch of a pertinent knowledge product from the SEA circular project.

UN Resident Coordinator in Thailand Visits Chonburi Province Dumpsite

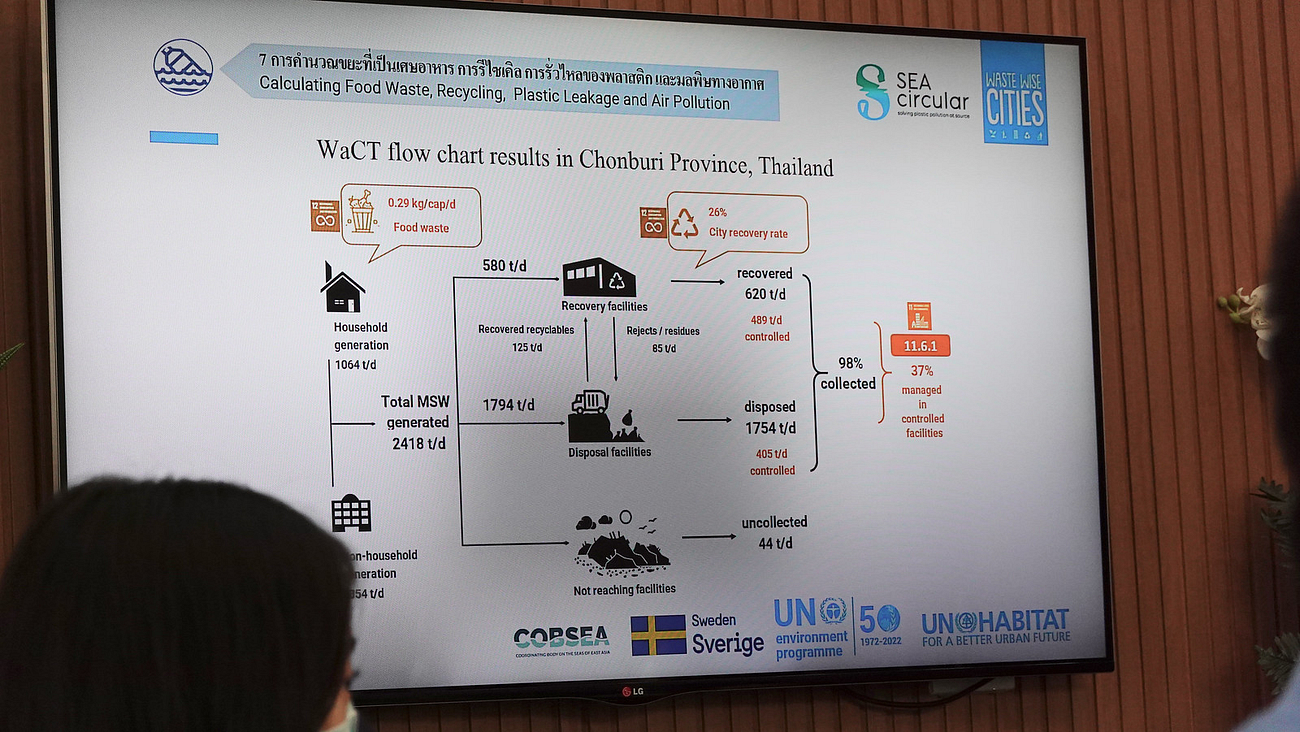

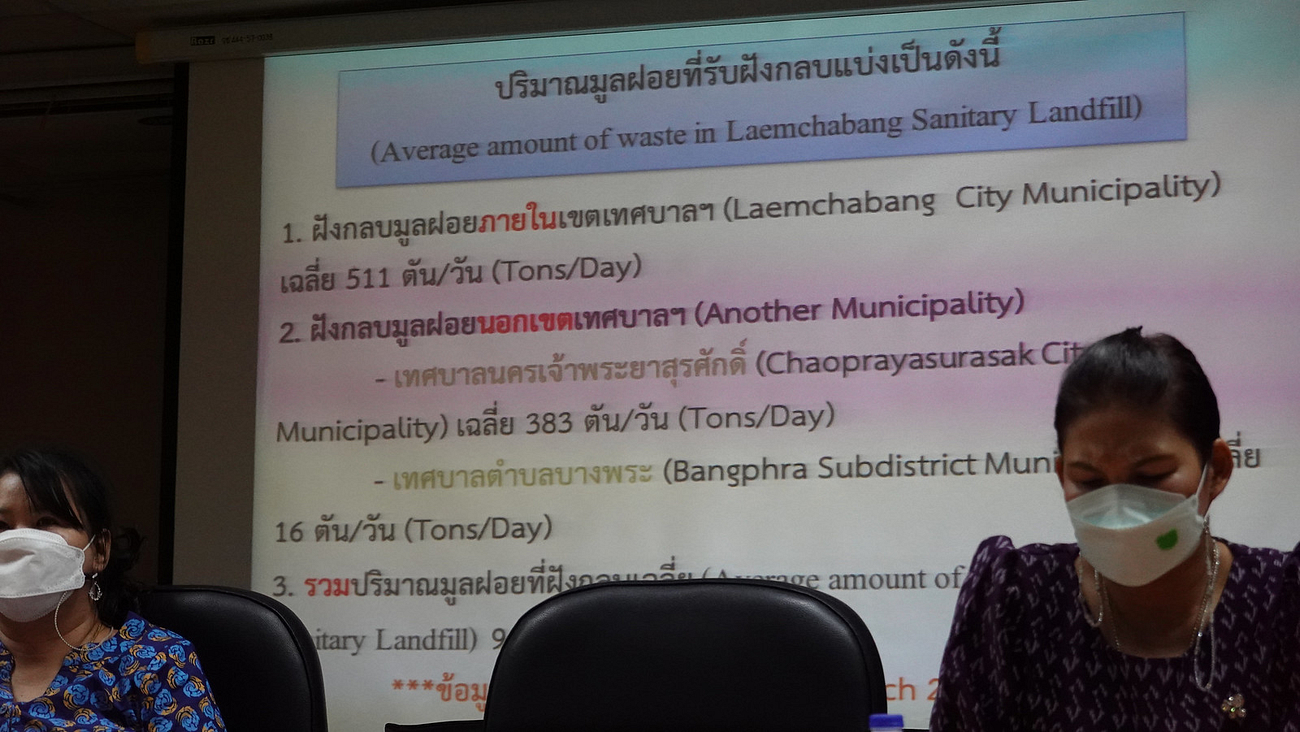

“Realising Bio-Circular-Green Economy targets will require Waste Wise Cities tool as well as community-led solutions. We cannot depend on dumpsites and landfills forever. Up to 800 tons of mostly household waste end up at Laem Chabang waste management site every day, which was just 500 tons per day two years back. Unless we change the way, we consume or manage waste, our planet will be swamped!

The United Nations Thailand has renewed support to Laem Chabang Municipality, including step-by-step guide to assess waste flows and leakage hotspots for better waste management planning. Next is also to study amount of emissions arising from dumpsites/landfills”, says Ms. Gita Sabharwal, United Nations Resident Coordinator in Thailand during her visit to the Laem Chabang Waste Management Site.

On May 18, 2022, UN-Habitat and UN country team organized a meeting with the Chonburi Deputy Governor Ms. Titilak and the provincial team to share the findings of the assessment on waste flows and leakage hotspot using Waste Wise Cities tool, which was conducted…